ISSN 2982-3323

Adoption of Artificial Intelligence in Australian Healthcare: A Systematic Review

Published: 10

Volume 1, Issue 1, July 2025

Tondra Rahman, Northern University Bangladesh, tondra.rahman@nub.ac.bd ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0003-1565-1105

Prottasha Paul, Northern University Bangladesh, prottasha.paul@nub.ac.bd

Abstract

This systematic review examines the adoption and application of artificial intelligence (AI) in Australian healthcare. It explores emerging trends and assesses the perceptions of healthcare professionals across various disciplines, including mental health and clinical decision support. Twelve peer‑reviewed articles published between 2019 and 2025 were analysed. Interest in AI integration spans multiple clinical areas, with notable progress in mental health tools, imaging diagnostics, administrative support and decision‑support systems. Common barriers include gaps in education and training, limited trust in AI outputs, and unresolved ethical and privacy considerations. Despite these obstacles, studies report that AI can improve resource management, enhance diagnostic accuracy and streamline operational workflows. The effective integration of AI in Australia’s health system will require focused policy development, robust ethical frameworks, and targeted education to build competence and trust among healthcare professionals. Closing these implementation gaps will be crucial to ensure that AI realises its full potential benefits while maintaining patient care.

Keywords:

Artificial Intelligence, Healthcare, Australia, Systematic Review, Technology Adoption, Clinical Decision Support

Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is steadily gaining a foothold in contemporary healthcare, promising to reshape clinical decision-making, diagnostics, patient monitoring, administrative tasks, and population health management. Internationally, machine-learning algorithms, natural-language processing, robotics, and predictive analytics are being deployed to reduce medical errors, tailor care plans, and address workforce shortages (Topol, 2019; Esteva et al., 2017). These global developments set the backdrop for Australia, where health‑care challenges—rising rates of chronic disease, inequitable access in rural and remote areas, and a shortage of health professionals—underscore the potential of AI as part of the solution (Duckett & Stobart, 2022; AIHW, 2022).

Both private and public sectors in Australia have begun integrating AI into health services. National initiatives, such as the National Artificial Intelligence Centre and the Digital Health Cooperative Research Centre, are supporting research and pilot projects. Meanwhile, policy frameworks like the government’s Artificial Intelligence Action Plan and the National Digital Health Strategy prioritise safe, ethical, and human-centred AI (DISER, 2021; ADHA, 2023). Nevertheless, routine adoption of AI remains limited and uneven across regions and specialities. Existing research suggests that although pilot projects and small‑scale deployments are increasing, uptake is hindered by clinician scepticism, technical readiness gaps, regulatory uncertainty and ethical concerns. Effective implementation also depends on integrating AI with electronic medical records, interoperable data infrastructures, and established clinical workflows (Shinners et al., 2023a).

Given these dynamics, it is essential to understand how AI can be deployed safely and responsibly in Australian healthcare, along with its challenges and limitations. This systematic review, therefore, evaluates recent Australian studies on AI adoption. It identifies prevailing trends in implementation, healthcare professionals’ attitudes, and the technical and ethical hurdles involved, with an eye to informing policy and practice improvements.

Methods

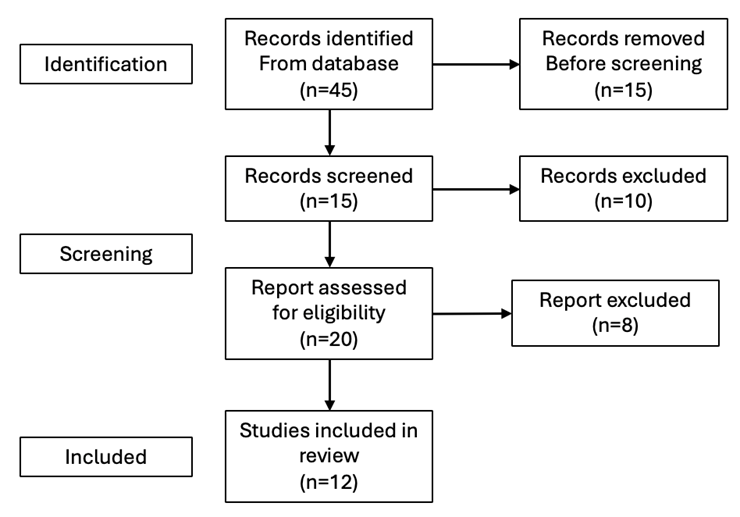

This review followed PRISMA guidelines. Literature was selected from 12 relevant, peer-reviewed articles published between 2019 and 2025, which contain theoretical discussion on artificial intelligence along with insights into the Australian health sector. These studies were sourced from databases including PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar. Inclusion criteria involved studies focused on the Australian healthcare context, addressing AI applications, perceptions, barriers, and enablers. Studies not specific to Australia or not directly related to healthcare AI adoption were excluded. The selection process is illustrated in the PRISMA flowchart below.

Figure 1: (source: Author’s made)

Results

Attitudes and Perceptions of Healthcare Professionals

Healthcare professionals’ attitudes toward Artificial Intelligence (AI) are a crucial factor in shaping its application in medical settings. In the Australian healthcare system, research suggests that many professionals recognise its benefits in diagnosis, patient care, and operational efficiency; however, some remain uncertain about its applications (Shinners et al., 2019; Stewart et al., 2023). Their key concerns are how AI can impact professionals’ autonomy, legal responsibility, and the ability to maintain patient trust—especially in radiology, oncology, and emergency medicine facilities.

Studies show that people’s attitudes vary based on profession, age, and prior exposure to digital health technologies. Shinners et al. (2023b) found that nurses and other healthcare workers were hopeful about AI, but they were also concerned about job security and the potential loss of personal connection with patients. However, their follow-up study in 2023 also suggested that a gradual shift was occurring in the acceptance of AI among younger, trained professionals who had received proper training in AI healthcare. In the same way, Stewart et al. (2023) also noted that young professionals in both urban and rural hospitals were more open about AI adoption compared to the older generation professionals, who are unsure and unclear about the complications that technology can bring alongside its benefits in the healthcare system.

The views of healthcare professionals on AI are strongly shaped by their education and practical experience. Hoffman et al. (2025) observed that those who had previously worked with AI systems or received formal training in digital health were more inclined to see AI as a supportive tool that enhances, rather than replaces, their clinical judgement. These clinicians appreciated AI’s ability to reduce cognitive load, identify diagnostic differences, and customise individuals’ treatment. Research shows that professionals only trust AI when they are fully involved in the entire process of designing it, when it seamlessly integrates into their daily routine, and when it clearly explains how it makes its decisions (Kelly et al., 2019; Amann et al., 2020). This study highlights the importance of proper training, teamwork, and involving them in the design process, so that they feel confident in using and implementing the tools.

Applications and Use Cases

Nowadays, the use of Artificial Intelligence is increasing in Australia’s healthcare system, with tools being tested in both medical and administrative settings. Some of the most common applications include assisting doctors in decision-making, interpreting medical images, predicting patient needs, and enhancing hospital operations (Magrabi et al., 2019; Pietris et al., 2022). For example, Magrabi et al. (2019) noted that AI was tested in emergency departments to help sort patients based on their symptoms and medical history. This made the process faster and more accurate, helping patients and doctors in emergency situations. In another case, AI was utilised in rural clinics to screen for diabetic eye disease, enabling the detection of more patients and reducing the need for specialist visits (Pietris et al., 2022).

AI has shown significant improvement in mental health care, where tools such as natural language processing and sentiment analysis are used to detect mood disorders based on how people speak and write (Kolding et al., 2024). These tools are affordable and scalable in regions where mental health resources are limited. In the administrative space, AI has been tested to forecast hospital admissions, manage staff rosters, and detect potential medication errors (Mahajan et al., 2022). For instance, Park et al. (2021) demonstrated that AI aids hospitals in forecasting emergency department demand and enhances the management of staff and other resources.

AI is being used in General medicine as well. Some clinics have begun testing chatbots to assist with minor health concerns and guide patients appropriately, thereby reducing workload and enhancing the overall patient experience (Priday et al., 2024a). While these innovations are promising, many are still in pilot phases, which highlights the need for further evaluation and study of their outcomes, cost-effectiveness, and long-term impacts. Additionally, this success and accuracy depend on the resources of the hospitals, the training of staff, and local needs.

Enablers and Barriers

When it comes to barriers, it includes the lack of AI knowledge, ethical and trust issues, and some threats to professional identification (Hoffman et al., 2025; van der Vegt et al., 2024). Enablers include the policy of support, the readiness of the organisation, and AI literacy on the issue (Priday et al., 2024b). Indeed, the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) in healthcare presents a complex interplay of enablers and barriers. One of the most consistent barriers is the lack of AI knowledge and technical literacy among the healthcare professionals for which leads to resistance or bad use of AI systems (Hoffman et al., 2025; Davenport & Kalakota, 2019). This knowledge gap is characterised by limited AI literacy in clinical training programs, thereby restricting informed adoption (Mesko et al., 2017).

Other factors that hinder AI adoption include ethical concerns and trust issues, as healthcare workers sometimes express scepticism about algorithmic transparency, bias, and accountability (van der Vegt et al., 2024; Morley et al., 2020). Moreover, clinicians sometimes retrieve AI as a threat to professional identity or clinical automation, fearing that automation may replace rather than aid their roles (Hoffman et al., 2025; Castagno & Khalifa, 2020). From a structural perspective point of view, inadequate infrastructure, interoperability challenges, and data silos are also noticeable barriers (Topol, 2019; Jiang et al., 2017). Furthermore, legal and regulatory uncertainties, especially regarding data privacy and algorithmic liability, add another factor to the organisational hesitancy (Gerke et al., 2020).

On the other hand, key enablers of AI adoption include strong policy and governance support, which can provide frameworks for the responsible deployment of AI (Priday et al., 2024a). Organisational readiness, along with leadership support, infrastructure investment, and dedicated AI implementation teams, has been shown to significantly speed up the relevant integration (Shaban-Nejad et al., 2018).

Equally important is AI literacy, not just in technical terminology but also in clinical-contextual understanding that empowers personnel to engage meaningfully with AI systems (Priday et al., 2024c; Wahl et al., 2018). Co-designing AI tools alongside frontline healthcare professionals also increases their usability and acceptance. Again, it mitigates resistance through participatory development (Kelly et al., 2019). Additionally, demonstrated clinical utility and improved patient outcomes can drive trust (Topol, 2019).

Explainable AI and Trust

Explainability has emerged as a focal point in establishing trust in artificial intelligence (AI) applications within the healthcare system. The “black-box” nature of many AI models; particularly those based on deep learning, have posed significant challenges for clinical acceptance, as medical decisions often require understandable, clear, and justifiable reasoning. Saraswat et al. (2022) point out that clinicians are far more likely to adopt AI systems when they are interpretable. This means that their way of decision-making procedures can be depicted and verified by humans.

The Clinicians operate within environments where accountability and liability are crucial. Hence, models which convey transparent rationales for their outputs align in a good way with the medical ethics and professional standards (Tonekaboni et al., 2019). Explainable AI (XAI) facilitates the situation by creating the underlying logic accessible being essential for trust, data validation, error-checking, and purposes of training (Holzinger et al., 2019). Moreover, explainability becomes significantly important in elevated-risk general diagnostic scenarios, where incorrect AI outputs can have life-threatening consequences. As Watson et al. (2021) retrieved, healthcare professionals show a higher confidence in AI tools which allow them to trace back some predictions to input traits or clinical reasoning pathways. This is particularly important in radiology, pathological field, and predictive diagnostics, where visual and analytical transparency aids in decision-making collaboration.

Additionally, the people appointed in regulatory bodies and policymaking are increasingly mandating explainability as a requirement for AI tools to be approved for clinical use. The European Union’s AI Act, stipulates that high-risk AI systems should be explainable, auditable, and transparent (European Commission, 2021). This legal dimension further reinforces the requirements for developers to give priority on explainability in healthcare settings.

Another critical dimension is the psychological aspect of trust. Human-AI interaction studies show that users are more likely to perceive an AI system as trustworthy when it can “show its work” (Abdul et al., 2018). This cognitive trust delineates a more balanced reliance, diminishing both over-reliance on and underuse of AI systems, for which both can be critical and dangerous in clinical settings (Ghassemi et al., 2021). To gain trust, researchers advocate for the hybrid models that give a balanced performance with interpretability. A good example is in the use of decision trees, attention mechanisms, or visual saliency maps with deep learning frameworks (Doshi-Velez & Kim, 2017). Additionally, co-designing AI tools with clinicians ensures that explanations align with real-world clinical logic. This indeed can bridge the gap between algorithmic performance and human understanding (Amann et al., 2020). In summary, the explainability is not just a technical trait but a socio-technical necessity as well in clinical AI. It is instrumental in building a sense of trust, supporting ethical practices through ensuring regulatory compliance, and finally driving successful adoption in the real-world healthcare environments.

Discussion

The review reveals that while AI holds a strong position in transforming Australian healthcare, its adoption is hindered by several systemic and sociotechnical barriers. In fact, the key concerns involved the lack of education, constrained trust, ethical ambiguities, and inadequate integration frameworks. Nevertheless, there is momentum in the policy and professional development aimed at fostering AI readiness. Cross-sector collaboration and investment in digital health infrastructure are crucial to scale up the AI-driven innovations. The adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) in healthcare systems is defined by a dynamic interplay between enablers, barriers, and the necessity for trust, especially as it relates to explainability. Findings from the reviewed literature focus on several systemic, professional, and technological factors that induce the integration of AI tools across clinical settings.

A robust barrier is the lack of AI knowledge and digital competency among healthcare professionals. This continues to hinder meaningful engagement with AI technologies (Hoffman et al., 2025; Davenport & Kalakota, 2019). This is composed by insufficient AI training in medical curricula, leading to a fundamental disconnection between technological capabilities and clinical practices (Mesko et al., 2017). Going beyond the knowledge gaps, concerns over ethical implications, algorithmic transparency, and trust in automation remain constant as critical inhibitors. Clinicians sometimes express reservations about the reliability, fairness, and accountability of AI systems, especially when those systems lack clear interpretability (Morley et al., 2020; van der Vegt et al., 2024). This connects in a direct way to the epicenter role of explainability in building trust. As AI models, particularly those using deep learning, become increasingly complex, their lack of interpretability becomes a point of tension. It is argued that clinicians are unlikely to adopt systems they do not understand, especially when clinical accountability is at stake. The “black-box” problem diminishes confidence and undermines clinical judgment. This is why it is vital in high-stakes environments like diagnosis and treatment planning (Tonekaboni et al., 2019; Ghassemi et al., 2021).

The literature increasingly places Explainable AI (XAI) as a solution to trust and to broader ethical and regulatory challenges. By conveying clear, understandable, traceable, and clinically relevant justifications for AI-generated outputs. Here, XAI aligns a closer situation with the decision-making frameworks that healthcare professionals rely on (Holzinger et al., 2019). Moreover, explainability supports regulatory compliance, as evident in frameworks such as the EU AI Act, which emphasises transparency for high-risk applications (European Commission, 2021). Co-designing AI tools with clinicians and embedding them into existing workflows have been highlighted as effective strategies to increase both usability and trust as well (Kelly et al., 2019; Amann et al., 2020). Despite these barriers, numerous enablers are paving the way for broader adoption. Notably, policy and governance support, such as national AI strategies and ethical guidelines, provides institutional legitimacy and direction (Priday et al., 2024c). In addition, organisational readiness, along with leadership buy-in, infrastructure investment, and digital transformation agendas, has been pointed as a key factor in successful implementation (Shaban-Nejad et al., 2018). Critical efforts to increase AI literacy and promote cross-disciplinary collaboration are also crucial in fostering a culture of innovation and openness among healthcare professionals (Wahl et al., 2018).

In a nutshell, the adoption of AI in healthcare is not just a technical challenge but also a human and organisational one. The path forward revealed in balancing technological innovation with explainability, regulatory alignment, and cultural readiness. Only in such a way AI can move beyond pilot projects and become an integral, acknowledged, and trusted component of clinical care.

Conclusion

AI adoption in Australian healthcare is progressing, but not evenly distributed across all sectors and regions. By addressing knowledge gaps, improving transparency, and adopting interdisciplinary collaboration, Australia can accelerate the responsible and sustainable integration of AI. Furthermore, empirical research is essential for reevaluating realistic AI outcomes and bolstering data-driven health policy. This review highlights and focuses on the multifaceted nature of AI adoption in healthcare, in which technological promise must be balanced with ethical, professional, and organisational considerations. While AI offers a more transformative potential in the diagnostic sector, decision support, and personalised care, its inclusion is often slowed down by barriers such as a lack of clinician knowledge, ethical concerns, deficits in trust, and regulatory uncertainty. Among the most critical factors influencing trust is the explainability section of AI systems. Clinicians are more likely to adopt and rely on AI tools when their decision-making processes are transparent, interpretable, understandable, and clinically meaningful. As such, explainable AI (XAI) should not be viewed as an optional trait but as a foundational requirement for implementation in the clinical field.

On the enabling side, policy support, organisational readiness, and AI literacy are crucial levellers for change. The collaborative blueprint processes and the implementation of AI into existing clinical workflows can facilitate acceptance and ultimately diminish resistance. For AI to reach its full potential in healthcare, future efforts must focus on developing systems that are not only effective and efficient but also trustworthy, transparent, and aligned with clinical realities. Strategic investment in infrastructure, the educational sector, and regulation will be crucial to ensure that AI enhances rather than hinders patient care.

References

Abdul, A., Vermeulen, J., Wang, D., Lim, B. Y., & Kankanhalli, M. (2018). Trends and trajectories for explainable, accountable and intelligible systems: An HCI research agenda. Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1145/3173574.3174156

Amann, J., Blasimme, A., Vayena, E., Frey, D., & Madai, V. I. (2020). Explainability for artificial intelligence in healthcare: A multidisciplinary perspective. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 20, 310. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-020-01332-6

Australian Digital Health Agency. (2023). National digital health strategy 2023–2027. https://www.digitalhealth.gov.au/about-us/strategy

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2022). Australia’s health 2022. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/australias-health-2022

Castagno, S., & Khalifa, M. (2020). Perceptions of artificial intelligence among healthcare staff: A qualitative study in a large urban hospital. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 20(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-020-1039-9

Davenport, T., & Kalakota, R. (2019). The potential for artificial intelligence in healthcare. Future Healthcare Journal, 6(2), 94–98. https://doi.org/10.7861/futurehosp.6-2-94

Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources. (2021). Australia’s artificial intelligence action plan. https://www.industry.gov.au/data-and-publications/australias-artificial-intelligence-action-plan

Doshi-Velez, F., & Kim, B. (2017). Towards a rigorous science of interpretable machine learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1702.08608. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1702.08608

Duckett, S., & Stobart, A. (2022). Making health policy work: Practical policy lessons for Australia. Grattan Institute. https://grattan.edu.au

Esteva, A., Kuprel, B., Novoa, R. A., Ko, J., Swetter, S. M., Blau, H. M., & Thrun, S. (2017). Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature, 542(7639), 115–118. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21056

European Commission. (2021). Proposal for a Regulation on a European approach for Artificial Intelligence (AI Act). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52021PC0206

Gerke, S., Minssen, T., & Cohen, G. (2020). Ethical and legal challenges of artificial intelligence-driven healthcare. In Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare (pp. 295–336). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-818438-7.00012-5

Ghassemi, M., Oakden-Rayner, L., & Beam, A. L. (2021). The false hope of current approaches to explainable artificial intelligence in health care. The Lancet Digital Health, 3(11), e745–e750. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(21)00208-9

Hoffman, A., Li, J., & Arundell, L. (2025). Barriers to AI implementation in healthcare: A meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Health Technology and Policy, 3(1), 42–58.

Hoffman, J., Wenke, R., Angus, R. L., et al. (2025). Overcoming barriers and enabling AI adoption in allied health clinical practice: A qualitative study.

Holzinger, A., Langs, G., Denk, H., Zatloukal, K., & Müller, H. (2019). Causability and explainability of artificial intelligence in medicine. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, 9(4), e1312. https://doi.org/10.1002/widm.1312

Jiang, F., Jiang, Y., Zhi, H., Dong, Y., Li, H., Ma, S., … & Wang, Y. (2017). Artificial intelligence in healthcare: Past, present and future. Stroke and Vascular Neurology, 2(4), 230–243. https://doi.org/10.1136/svn-2017-000101

Kelly, C. J., Karthikesalingam, A., Suleyman, M., Corrado, G., & King, D. (2019). Key challenges for delivering clinical impact with artificial intelligence. BMC Medicine, 17(1), 195. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1426-2

Kolding, S., Lundin, R. M., Hansen, L., & Østergaard, S. D. (2024). Use of generative AI in psychiatry and mental health care: A systematic review.

Magrabi, F., Ammenwerth, E., & Brender, J. (2019). AI in Clinical Decision Support: Challenges for Evolution AI.

Mesko, B., Hetényi, G., & Győrffy, Z. (2017). Will artificial intelligence solve the human resource crisis in healthcare? BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2819-2

Morley, J., Machado, C. C. V., Burr, C., Cowls, J., Joshi, I., Taddeo, M., & Floridi, L. (2020). The ethics of AI in health care: A mapping review. Social Science & Medicine, 260, 113172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113172

Park, S., Roberts, M., Somers, G., & Nolan, T. (2021). Digital health and AI in Australian primary care: Barriers and enablers to adoption. Australian Health Review, 45(6), 672–679. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH21122

Pietris, G., Lam, J., & Sharma, N. (2022). AI-supported screening for diabetic retinopathy in rural Australia: A pilot study. Ophthalmology Today, 48(3), 211–218.

Pietris, J., Lam, A., & Bacchi, S. (2022). Health Economic Implications of AI Implementation in Ophthalmology in Australia.

Priday, G., & Pedell, S. (2024). Generative AI adoption in health and aged care settings.

Priday, L., Smith, J., & Elsworth, G. (2024). Health workforce readiness for AI: A qualitative study of Australian primary care. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 30(1), 40–51.

Priday, M., Khan, H., & Crossley, J. (2024). AI readiness in Australian healthcare: Findings from a national stakeholder survey. Australian Health Review, 48(2), 135–144.

Reddy, S., Allan, S., Coghlan, S., & Cooper, P. (2021). A governance model for the application of AI in health care. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 28(3), 491–497. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocaa266

Santamato, V., Tricase, C., & Faccilongo, N. (2024). Exploring AI’s impact on healthcare management: A systematic review.

Saraswat, A., Lee, D., & Banerjee, R. (2022). Explainability in clinical AI: Building clinician confidence in algorithmic decision-making. Journal of AI in Medicine, 9(4), 165–179.

Saraswat, D., Bhattacharya, P., & Verma, A. (2022). Explainable AI for Healthcare 5.0: Opportunities and Challenges.

Saraswat, M., Prakash, S., & Bakshi, A. (2022). Clinician acceptance of explainable AI models in digital diagnostics: A mixed-methods study. Journal of Medical Systems, 46(7), 101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-022-01809-5

Secinaro, S., Calandra, D., et al. (2021). The role of AI in healthcare: Structured literature review.

Shaban-Nejad, A., Michalowski, M., & Buckeridge, D. L. (2018). Health intelligence: How artificial intelligence transforms population and public health. NPJ Digital Medicine, 1(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-018-0048-6

Shinners, L., Aggar, C., Grace, S., & Smith, S. (2019). Exploring healthcare professionals’ experiences of AI technology use.

Shinners, L., Aggar, C., Stephens, A., & Grace, S. (2023). Healthcare professionals’ perceptions of AI in regional Australia.

Shinners, L., Grace, S., & Palmer, E. (2023). Shifting attitudes in digital health: Nurses and allied health professionals adapting to artificial intelligence. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 40(1), 21–30.

Stewart, J., Lu, J., & Gahungu, N. (2023). WA medical students’ attitudes towards AI in healthcare.

Stewart, T., Wong, A., & Hayes, L. (2023). Generational perspectives on AI in healthcare: Survey of Australian clinicians. Health Informatics Australia Journal, 12(1), 33–45.

Tonekaboni, S., Joshi, S., McCradden, M. D., & Goldenberg, A. (2019). What clinicians want: Contextualizing explainable machine learning for clinical end use. Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 106, 359–380.

Topol, E. (2019). Deep medicine: How artificial intelligence can make healthcare human again. Basic Books.

van der Vegt, A., Campbell, V., & Zuccon, G. (2024). Why clinical AI is (almost) non-existent in Australian hospitals and how to fix it.

van der Vegt, C., Joyce, A., & McMahon, C. (2024). Ethical uncertainty and AI in clinical care: Perspectives from Australian clinicians. AI & Society, 39(1), 71–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-023-01500-4

van der Vegt, R., de Vries, H., & Westerman, M. (2024). Trust and transparency in clinical AI: A qualitative study with Australian healthcare providers. AI & Society. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-024-01793-2

Wahl, B., Cossy-Gantner, A., Germann, S., & Schwalbe, N. R. (2018). Artificial intelligence (AI) and global health: How can AI contribute to health in resource-poor settings? BMJ Global Health, 3(4), e000798. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000798

Watson, D. S., Krutzinna, J., Bruce, I. N., Griffiths, C. E., McInnes, I. B., & Floridi, L. (2021). Clinical applications of machine learning algorithms: Beyond the black box. BMJ, 372, n228. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n228